The BOONESTAIL ENCOUNTER of 1809

INTRODUCTION:

IN 1842, DR. ISAIAH HORNE WAS INTERVIEWED BY A SECRET BRANCH OF THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT FORMED BY THOMAS JEFFERSON DURING HIS PRESIDENCY (1801-1809). THIS AGENCY (ITS NAME LOST TO HISTORY) HAS SPARSE RECORDS RANGING FROM 1801 TO 1865, WITH MOST DOCUMENTS DESTROYED DURING THE CIVIL WAR, WHERE SEVERAL CITIES CONTAINING ARCHIVES WERE BURNED TO THE GROUND.

MODERN RESEARCHERS HAVE FOUND LINKS BETWEEN ITS OPERATIONS AND THE 1947-FOUNDED NATIONAL AGENCY OF PARANORMAL INVESTIGATIONS.

DR. HORNE WAS INTERVIEWED IN HIS DIRECTOR’S OFFICE AT THE CAWTHON SANITORIUM IN MARLYAND. AFTERWARDS, HE WAS ASKED TO WRITE A SUMMARY OF THE BOONESTAIL, MISSOURI EVENT IN 1809, IN WHICH HE RECALLED JOURNAL NOTES FROM THE TIME.

Some language and dialect-specific words have been changed or modified by the previous typesetter(s) with several edits over a period of three to four decades. The freshest set of edits occurred sometime between 1893 to 1910.

This slight doctoring of the summary includes several passages marked through with heavy ink lines (leaving them unreadable/unrecoverable), ‘X’ marks on certain words pertaining to fungi and slash marks through the mild use of profanity throughout Horne’s summary.

***

JUST BEFORE SUNSET ON NOVEMBER the Tenth, I was packing up my tools and sorting loose paperwork at my office on Fifth Street. At the time, I was an unmarried doctor of twenty-six and had lived in Boonestail since 1805 after graduating from Columbia University in my home state of New York. My days were usually quiet, but once a month or so, a quiet afternoon would be punctured by the broken hand or leg of a logman. November the tenth had been one of those days—Mr. Herthman, a barrel-chested logger older than the town itself had fallen from his ladder after a branch snapped from under his feet. His handsaw had fallen with him, digging into his thigh once they both reached the ground. And after a few hours of whiskey swigs, screaming, stitches, and lots of blood spurting, I wrapped Mr. Herthman up and was done with gore for the evening.

Much has changed in the medical field since the start of the century and I was always weary of the fact that we were out of our element. Besides the occasional logging injury that was to be expected, I treated toothaches, sore backs, and general bad moods with prescriptions for liquor or an equivalent nullifier of pain that came in a small brown bottle. While opium had yet to reach the walnut tree-filled backwoods in 1809, I was lucky enough to have to the assistance of a benevolent Wiccan who provided me with extensive and fresh batches of medicinal herbs that sufficed in a time when opium and other miracle pain relievers were not commonplace in the Midwest.

I stepped out into the lamplight that showered the front of my office and often tricked me into thinking I had some daylight left. The sun had vanished and the chill of winter stuck to my foggy breath. I was eager that evening, on my way to meet the Wiccan at the apothecary shack that doubled as her home on Lance Street. Rumors flew wild in town that the brash but brilliant town doctor was in an unlawful relationship with the witchy woman of tanner skin than the rest of us. But the truth was much less exciting— we met for a nightly ‘study session' as she referred to it, where we would exchange stories about our strangest and most difficult patients while she mashed some new concoction of soothing herbs and mint.

I enjoyed those evenings, moreso that winter as I was beginning to feel homesick, often dreaming of my family’s home, a magnificent estate overlooking the Hudson (River) near Apthorpe Mansion. I spent many nights voicing my woes to her and she was the best kind of muse. The Wiccan was a kind voice behind my rattled thoughts, often sitting in silence with her mortar and pestle, only interjecting with the most carefully selected words.

I still think about those nights. They were the best part of living in Boonestail, I must say.

But anyhow, I would not meet the Wiccan at her shop. Out of the darkness past the streetlamp, the kind-faced but worried Sheriff Tiberius emerged. He was a stern brick wall of a man, dressed in dark blue office regalia as always. He tipped his hat in a half-hearted gesture as he approached. He had summoned my presence to the church—inside was the body of a strange wild woman that attacked two boys in the woods outside of town hours earlier. Her appearance was “almost dead but not quite” and “inhuman-like” according to the sheriff, her skin pasty green stuffed with twigs and branches and her arms elongated like twin snakes. The night had become chillingly still, and it became apparent that falltime had fully settled in. By the time the sheriff had finished his curt, expressive recollection of the boys’ story, a more primordial chill started to gnaw at my bones.

We crossed the freezing muddy street and went down the winding path lined with hedges past Ames Farm Supply and the local inn. The stars had just begun to twinkle when we were met with the rusted metal gate that closed off the town from the Sanctuary of the Holy Brethren. There never was an official denomination given but based on my recollection, Pastor Oaken was the silver-haired head of a plain Lutheran church, only its bricks were forged in place by raging Baptist fire.

Pastor Oaken greeted me at the main doors with a glare of blasphemous disgust and I returned it with the brightest smile I could muster in the moonlight. He had a palpable energy about him that made it obvious why he was respected amongst the people of Boonestail. His giant hands and cabinet-sized Bible made him look like a religious folk hero. He preached the good Word and acted upon it by all accounts, coming to the aid of several children trapped in the schoolhouse on Brook Street in 1803. The center beam had collapsed after a bad ice storm and four children were trapped inside as the stove spilled hot coals across the wooden floors. Oaken had ran inside the fiery schoolhouse, broke through the smashed pillar with a shovel and carried the children out of the blaze on his back. I respected him for that but he never liked me.

He played the part of a town legend well, standing six foot seven and always seen with his trademark black Geneva gown. To me, that made him come across as an underworld ghoul rather than servant of God.

Our nonchalant meeting felt more like an invitation into a doomed dungeon. Luckily, the sheriff was there to shake the pastor’s hand, pat him on the back, and protect me from the man’s glare. I had to stifle back laughter. Although it was clear why he hated me (I was a staunch open-atheist doctor with dreams of redesigning the well water system and taking money away from the church), his taunts were never more than the whistling heat of passive-aggressive squabble on my “lack of beliefs yet unyielding faith in science”.

I would later learn from Oaken that the circular beams that made up the church’s entrance were “from the stern of a Pilgrim ship that came shortly after Plymouth’s settlers”. I hadn’t been one to frequent the church of Boonestail on Sunday or their middle-of-the-month feast days—they appeared secular on the surface until Oaken emerged from the dark church cellar with palms hungry for coin rather than a bowl of gruel. But despite my avoidance of religion in general, I did admire the craftsmanship of the woodwork. It allowed the quaint church that could house fifty people to appear as a mass worship temple, angled toward the milky night sky like a European cathedral. Made of historical ship stern or not, Oaken used that beggared coin to the best of his ability, at least where good varnish and crucifix carvings were concerned.

As I ducked under the solid arm of the pastor and he pulled the doors shut, a pungent mix of sweet red wine and heart pounding sour-ness sent me aback. The smells became stronger as the candlelight that hazed in a sickly orange exposed the harshly splayed corpse strapped to the jewel adorned chest reserved for taking communion.

“I sent the young ones home,” Oaken said, walking to the pews and staring out the red stained glass windows. “They don’t need to be a witness to this brutality.”

I agreed, with the suggestion that we needed to get the boys’ official statement later. Oaken’s face went red, questioning my authority in the house of God and in the presence of Boonestail’s sheriff. When I turned to Tiberius for reason, he returned a look that let me know there might not be an official report. I turned my eyes to the stage, greeted by an odd assortment of townspeople observing the body in morbid curiosity.

Mick Ames of Ames Farm Supply down the street was sloppy drunk with his shiny silver flask in hand, leering over the body— staring directly at the corpse’s breasts, or where breasts should have been on the feminine figure. On the opposite side of the stage were the Hudson brothers, a trio of young carpenters who were always friendly and ready to give a helping hand for anyone’s home repairs. They were hunched over, like they all shared a stomachache, whispering amongst themselves.

The sheriff’s nephew was standing against the chest, his legs crossed as he smoked a pipe with nervous hands. His heavy wet boots were stepping on the curtain draped across the twig-filled corpse’s lower half. I asked him to take the pipe and its thick smoke elsewhere (in my kindest tone of voice). He stared at me with tired red eyes and then looked to his uncle—Tiberius stood beside me and gave me a leading pat on the back. The deputy rolled his eyes and held the pipe in his mouth, dusting grit off his trousers and squeaking his wet boots down to the pews.

And out of the darkness of the pastor’s quarters at the far left end was the Wiccan, her hands freshly scrubbed and her eyes shining with relief. We exchanged pleasantries with a look and Oaken rose to the stage, beckoning us both.

Pastor Oaken explained to me that when the boys brought the body in through the back door, it was “wheezing and thrashing about.” The boys had been hunting quail and turkey in the deep woods before nightfall when they watched an elm tree “breathe deeply”. The youngsters then heard the cat-like laugh of a spindly woman who was “swinging from branches and howling up some fifty-feet high”, appearing light as a feather. She was naked and dirty, flying across the treetops like a fish flopping in a strong current.

The younger boy, Thomas, told Oaken that the woman vanished into a puff of smoke before she leaped out of the ground in front of them like a malicious magician. She began to run at them on all fours and Edward, the twelve-year old, aimed his musket at the woman’s bare chest. A single shot mid-sprint hit her in the heart. She tumbled to the ground, writhed in pain, and a bubbling froth of dark red and white fluid spilled from her lips. But she was still breathing. So the scared boys used the bundle of twine for their hunting kills to strap her arms and legs and drag the monster woman carefully over the hour-long stretch to reach Boonestail. Thomas had said that the body went fully limp at sundown. So I estimated death at around five in the evening.

The boys had stopped by Mick Ames’ shop through the backyard. The scared and confused farmer quickly ran to his closest confidant, Oaken, who urged him to bring the forest woman into the church. In the meantime, and against his better wishes, Oaken realized that he needed all of the medical knowledge available, which came in form of the Wiccan’s herbal expertise and my modern tools.

Upon my examination of the corpse at 6:20PM (and two rough sketches of the body) I was taken aback by the alien texture of the hairless skin. It was indeed a light shade of green, like a vibrant celery stalk. Across the scalp, through the cheekbones, and down the sides of the neck and shoulders were hundreds of tiny twigs and sticks, all broken apart and stuck into the skin. While some could have been gained during the body being dragged through the woods, most of the thicker twigs appeared to be intentional punctures, dagger-shaped pieces of birch tree bark. I noted that the wounds could have been self-inflicted and that the palms were littered with dark splinters.

My mind recalled the soft, almost rubbery feeling of mushrooms without conscious effort. I shook the thought away but on observing the corpse’s skin, the fungal thought hung around. Besides the roughed-up nature and several deep masses of bruising along the torso, arms, and back, it appeared human. It was womanly in shape, with definitive child-bearing hips, around five foot two inches tall and weighing approximately ninety-eight pounds. The eyes were of a drying jelly consistency, golden-brown in color behind the creamy film of mortis. The corpse appeared to be sleeping peacefully, save for the heavy ligature marks around the wrists and having the appearance of rolling down a rocky hillside.

After my initial shock, the arms presented the first true peculiarity. The upper arms were much longer than the average woman, causing the hands to stretch down five inches past the waist while laying supine. One of the boys had tied the woman’s wrists together and the large thumb indents from his hands were still visible hours after death. This made initial attempts at finding a vein difficult, as the skin was divided into many layers, thicker than subcutaneous fat. Pressing my thumbnail into the skin was akin to a cold, soaking wet rag. When I released, the flesh stayed in place. At that moment, I had noticed that the wind had picked up, the dead breath of winter howling upon the church.

The corpse’s mouth had been tied shut with a fresh piece of linen, little fluffs of the new fabric covering the stage as I removed it. The lower jaw began to open slowly—rigor mortis had not fully set in, solidifying my estimated time of death. Now agape, the corpse’s mouth had roughly twenty teeth, deeply black and filed to points, specifically the canines. The lower molars were gone, replaced with a thin strip of reflective metal on either side of the mouth, stamped and seared into the gums. Raised lumps of scar tissue could be seen along the gum lining, puffy calcified bits of burnt skin resting into place.

The tongue had retreated backwards and I used forceps to pull it forward, exposing dozens of raised black veins across the surface. Each vein was connected to a web-like structure on the roof of the mouth. The inner throat was dry and crusted over near the area where the tonsils would normally sit, bundles of black veins packed into the corners. It puzzled me—how could this creature speak to the two boys? Or simply eat food? The filed teeth suggested a harsh diet of some kind, filling my mind with stories of cannibalistic monsters hiding in every forest from Missouri to Tibet. It was all rubbish, of course. But every glance at the corpse sent me spiraling further into a childlike state of wonder. Magic existed, if for a brief moment.

After I finished my examination of the head, Oaken emerged from the shadows of the stage to berate me, holding the discarded linen like the Shroud of Turin. He spoke of ancient natives who could destroy a man’s mind with simple words, hence the tying of the mouth. I shoved off his mystical suggestion by asking for a glass of water and continuing my procedure. Oaken stomped off, muttering about “witches” and “corrupted bodies needing to be burned.”

It became clear that while the corpse had bones and ligaments like our own human anatomy, the body lacked any recognizable organs, save for eyes, the tongue and various mucus membranes such as the sinuses and sex organ. I assessed the abdominal area, feeling a hollow cavity where the intestines should reside, and realized that the external examination was fruitless. I proceeded with open autopsy at 6:35PM, armed with a scalpel, a shaking Christopher holding a lantern close, and the sheriff’s nephew judging us in silence.

On the first incision across the upper right quadrant near the kidney region (my first operation post-medical school), the first layer of skin peeled apart, receding and rolling over itself to reveal pale-white tissues, no blood—only a thin coating of pale yellow fluid from the secondary layers. The smell, was not that of rotting flesh, but earthy, as if from a dug up mound of rich soil in a worm-filled forest. The tissues were simple in nature, resembling fat but with much larger cell walls, honeycomb structures mashed together in unison inside the moist, spongy material. So, this corpse was more plant than person, as people do not have cell walls. After explaining this to the people in the church, the whole room became cold at the sight of something that had been masquerading as a human being.

I was entranced. Just a few hours earlier, this creature had supposedly been up and about, climbing trees fast as an animal and floating about the sky like a wraith of legend. Whatever its goals had been, whoever it called friend or foe, none of it mattered now—I almost felt ashamed at my investigation. Despite the corpse clearly not being human, I felt a growing sense that this was nothing more than butchery of something I couldn’t comprehend. And for once, the thought crossed my mind that maybe Oaken was right.

By 7PM, an unusual first frost had broken into the church, wafting through the cracks with a damp chill. Two of the Hudson brothers, the eldest Ira and youngest William went off to bed. Ames was half-asleep but no one wanted to bother him as he slept on the front pew. Christopher, the middle Hudson brother of eighteen was fascinated by the autopsy, eager to grab a specimen jar or wash a scalpel when the gore turned thick. Besides Oaken and the policemen standing guard and challenging their view on reality, Christopher and the Wiccan became my only assistants as I continued dissection and fed my fascination.

Truth be told, this was the unspoken dream of any true doctor that worships the human form. But as the scalpel split through spongey flesh and I found nothing but hollow cavities where organs should lay, I came to understand this woman-thing was not human in the slightest. More of a plant-based clump of pure nature material molded into the familiar shape of a person. The cavities were quite large, hollow except for the yellow fluid that seemed to function as an insulator. It was slightly warm upon touch and the cavity fluids were noticeably gritty in texture rather than the runny liquid that billowed from the dermis. A morbid part of me wondered if the soft skin could be penetrated without causing harm, a reasonable guess based on the large sticks stuck in the corpse’s flesh by its own hand.

I once again checked the corpse for veins, starting at the long wrist. I made a small slice down the center of the right forearm, the flesh peeling back the same as the torso. During the first cut, I felt the blade scrape across several spherical objects embedded deep in the flesh. I used a set of forceps to push the sides of the forearm apart, the metal hooks parting to reveal four neatly packed objects that the Wiccan referred to as “strange walnuts”.

The ‘walnuts’ were around the same size as their namesake, but dark green in color, like the shades one would see at an undisturbed lake plagued by algae. While the outer shell was tough, it was slathered in a lard-like substance that drifted around the surface of the sphere like oil separating from water. The swirls of nature green and golden yellow were mesmerizing and as I brought one of the walnuts to my eye, I felt an intense burn snake down my arm.

The yellow slime sizzled with a white-hot heat and I dropped it while backing up from the chest. My arm went fury-red in an instant and I watched the fluid drip off my elbow and splatter on the floor. The Wiccan kicked the rolling walnut from the stage, smoking through the floor as I grabbed the curtain from the corpse and began wiping the scorching toxin away.

The walnut bounced down the stairs and exploded into a mist of golden yellow, a shower of tiny feathery orbs drifting across the expanse of the church. Pastor Oaken opened a window quickly, appearing from behind the stage with a cloth wrapped around his nose and mouth. He believed that the yellow mist (which had no scent or effect once it floated its way toward the stage) was a toxin, perhaps a defense mechanism for the human-looking plant. Christopher said the name first—“pellet round”. The Wiccan agreed that it was better than calling them walnuts.

We applied a cooling mint salve to the four pockmarked burns and wrapped my arm in a bundle of linen. I assured myself that the strange coating had not dissolved further into my flesh and I decided to return to the dissection, ever more careful of the pellet rounds.

Perhaps only because I was performing this unholy ritual in a church, I was reminded of a Bible verse from the book of Genesis—“And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul".

I thought about the Greek myths, gods forming humans out of clay. A mold. And then the realization hit me like a Eureka bolt of lightning straight from Zeus himself. The tissues were not unlike mold. Not unlike a fungus. Is that all this creature was? A walking, talking, laughing plant? And the pellet round. The yellow mist was similar to pollen spores, spreading the seeds along the wind. It was quite a windy night.

My mind was racing but I had no further time to deliberate as the front doors to the Sanctuary blew open, washing us in a shock of red wine and fresh meat. The Wiccan attempted to shield the corpse with the curtain, draping it over the upper half and rolling up my bag of medical tools. I ducked behind the chest with her, glass showering the stage as the back windows shattered and a flurry of cackles echoed into the church.

The laughs were malicious, followed by sharp taunts in an unspoken language not meant to be understood. I closed my ears with my hands, watching the panicked men look all about the church as the lights were snuffed out. The Wiccan held onto the corpse, almost embracing it as the wind sent more objects flying. Christopher emerged from cowering in the corner of the room to help her keep the corpse safe. The front doors crashed against the small lobby walls, smashing the welcoming table and sending Bible pamphlets into the air.

THE SACRED hollow is in danger…

A curse has fallen upon the stronghold of Mendac witches in colonial North America.

The leaders conduct a time-sensitive mission to stop the curse from spreading into a corruptive force that holds no mercy for magical being and mortal alike…

Click the NERVOUS WITCH gif to read more!

A swarm of leaves rained sideways at us like hungry locusts, even stirring Ames from his drunken sleep on the pew. The sheriff started running to the swinging doors and urged me to help, the smell of rich wine becoming fumey and disorienting. I leapt from the stage and made my way down the aisle, cold moonlight guiding my way as all light was swamped from the church. Pastor Oaken was behind me with wet eyes and pursed lips, marching to the door like a militant angel at Heaven’s Gates.

“I brought that thing into the church because I didn’t want the rest to be corrupted!” Oaken exclaimed, budging the doors shut and wedging a large candlestick inside the door handles. “But this has gone too far, doctor! We burn the corpse! Now!”

Oaken made his way to the stage, holding an arm out as the darkness poured in from the shattered windows. The Wiccan and Christopher still clung to the body and an argument broke out when Oaken tried to take the curtain. The sheriff’s nephew knocked her from the chest and ripped the curtain away, the corpse stark white in the dark. Brave Christopher punched the young man in the face and sent him to the floor. The sheriff and I ran to the stage, tripping over Mick Ames as he crawled down the aisle in confusion, screaming about his missing flask. All had fallen apart in a matter of seconds.

More laughing boomed from outside, different voices taking turns as the sounds pierced through my head. It was as if the voices had covered the church like a steady rain. There was an awful rumbling that shook through the remaining windows and rattled the debris of wood, glass, and leaves scattered about. I crawled up the stage as a wild-eyed Oaken stood behind the chest, furiously tying the corpse’s hands together, like a body prepared for a funeral pyre.

“In this town, Doctor Horne…” Oaken screamed at me from his makeshift pedestal. “We do not let the wicked fester!”

Oaken prepared to burn the corpse, revealing the stolen flask of Mick Ames, still halfway full of fiery Missouri moonshine. The pastor lifted the flask to the howling night sky like a communion goblet and poured the liquor over the body. Oaken finished by gifting the last bit into the corpse’s open mouth, tossing the flask aside and reaching inside his robe. He withdrew a matchbook and against the biting winds, the match lit up on the first stroke. Oaken’s lips parted for a final speech, but nothing was heard over the deafening blast.

A green fireball exploded through the front doors, tearing them from the hinges and launching them into the back rows of pews. Wood splinters flew as if from a cannonball shot and the pressure of the blast sent one of the doors down the right column of seats in a cartwheel fashion. The fireball was neither hot nor cold, maintaining its monstrous overlapping stream of green and white flame as it traveled down the center aisle, washing over the mortified Mick Ames without harm. Oaken’s tiny flame snapped into nothingness as he was sent flying to the back of the church.

The Wiccan had come to, grabbing my arms as we steadied to our feet. She too was doused in the spilt moonshine, yet unharmed by the alien force. The fireball had been a false flame. Perhaps a hallucination, as a result of the pellet rounds’ dispersed mist. I struggled to gather my thoughts, my head clouded by the everpresent noise, heavy smell of intoxicating booze, and the realization that we were facing a danger for which I had no reference. Recalling these events from nearly a quarter of a century ago has brought about the resurgence of I felt during the latter half of that night: utter terror.

The dark ends of the high ceiling shifted and the wood beams creaked. There were at least three figures wedged into each corner—the creatures had been watching us for God knows how long. I could only imagine their rage. Cutting up a member of their supernatural society with barbaric dissection. But why didn’t they retaliate sooner? Why now?

Within a single breath, the shadowed husks sprung to life, gliding to the floor like dead leaves catching the breeze. In the flashes of moonlight from the rocking trees outside the church, pale green fingers stuck out from the edges of the robes. Although more than twenty paces from us, their grassy black robes were so heavy with pungent mold and aged earth that I could almost taste them. The three or four figures raised their arms, synchronized like a deathly band march, followed by the sound of a whistle. A flurry of pellet rounds bounced around the room, popping into yellow seed mist and spitting out fiery droplets of toxin. Fabric on the church pews caught fire, little wisps of smoke jetting up. The rotten stench was thick. Mick Ames was crammed underneath one of the smoking pews, trying to blow out the embers, unfazed by the figures. The sheriff was leaning against the busted open window near the stage, almost unconscious from exhaustion. And Pastor Oaken was in front of the chest once again, preparing to light another candle.

I tried to stop him, reaching across the stage but Oaken threatened me, striking the flint and catching the wick alight. His eyes burned along with the dense orange flame that grew around him like a furnace of hate and fear. The figures hissed together, prickled gooseflesh poking into my collar. Oaken dropped the flintstone, his hands shaking but his head still held high. This was quickly becoming a deadly confrontation. One that ended in fire and blood. And yet, I couldn’t speak. My mouth was dry and the toxic pains in my burned arm seemed to leap about the craterous wounds, turning me queasy. Luckily, I wasn’t my own savior that night.

“The body is not ours! We give it to you!” the Wiccan screamed as they approached the steps, towering over us in mossy drapes propped up at odd angles, like a hunched six-foot lizard hid beneath the natural garments.

I looked at her and almost retaliated. I felt shame. And anger. I was basking in the glory of unprecedented medical discovery, planning my future book title and a list of publishers in my head the entire macabre evening. But it was all moot in the face of real magic, dare I say. And I could comprehend almost nothing about it. And so, I relented to my wiser compatriot.

“We… want… our… sister. No… harm… to you.” the voices said in unison.

Relief began to wash over me. Their mirrored words were not malicious in tone. Certainly harsh and tinged with a quivering resentment, but truthful nonetheless.

“Please,” the tallest of the figures said, holding its large hands out. “She was only playing with the children. She meant them no harm.”

The moonshine glistened on the corpse, like on lake waters as the body seemed to breathe once again. Oaken’s face softened for the first time in my life. He shook the candle, ending its short life, and tossed it to the side. He relented and stepped away from the chest, but not before a small, half-hearted rebuke. “Now take the corpse, witch! Be done with us!”

The corpse screamed out, twigs snapping apart at the shoulders as her heavy arms slapped about the chest. Her raspy voice croaked out of her split-open throat in wails of ear-ringing pain. Oaken ran from the chest, pushing me and the Wiccan away as the sheriff’s uncle stood frozen, his musket’s ramrod stuck in the barrel aimed at the corpse. The power in the corpse’s movement was unbelievable— the front of the chest rendered into sawdust after a few slams. It cracked under the weight, the corpse flipping onto the stage as the robed figures approached, parting the yellow, sparkling haze.

A small voice entered my head, urging me to take ten steps back. The voice must have been communal because the Wiccan and Oaken moved with me without prompt. The sheriff and his nephew relaxed their posture and slumped to the ground softly, the half-loaded musket standing upright on its butt.

The floors groaned and we watched in awe as the brown varnish was drained away into a greasy thick vapor. The brown and yellow colors began to recede, pulled into the thrashing corpse and leaving the wood pale. The stage followed suit, the colors rushing under my feet and entering the moving corpse as hundreds of tiny wooden splinters sliding underneath the fingernails, the dermis, and into the empty cavities. The color drained from the room and the corpse became someone anew—a bright-eyed gaunt woman with flush red cheeks and the splayed-out sections of flesh now sealed with bright yellow sinew. She was quickly covered with a smaller robe slathered in mushy green lichens and mossy growth—embraced by the other hooded figures with archaic whispers and gentle head touches.

“I’m sorry.” I stupidly said. “We assumed that you were dead.”

The corpse looked at me, her golden eyes now shining bright amber in the dark. “You said that we… are not like you.” the corpse then mustered something akin to a smile, as if hooks were dug into the sides of her mouth to pull them upward. “If that is true, would we die the same as you?”

I had no answer.

The head figure stepped in front of the corpse—it bowed before hissing loudly, gleaming jagged teeth poking through the darkness of the hood. I reared back, which appeared to be an acceptable gesture as the the figure nodded slowly and guided her ‘sister’ to the window. The wind began to fade and all of the awful scents of the night began to drift as well. A renewed warmth entered the room and just as I began to recall the witch’s final words, my vision went dark.

***

When we awoke, the next day had dawned. The sheriff and his nephew could not recall much, only the vaguest detail about a dead woman found in the woods and some kind of awful wind storm. Mick Ames awoke with the belief that the group of us had tricked him into drinking moonshine and left without an inclination of the events. Christopher thought it all to be a nightmare, convinced that he had eaten a bad possum stew. But the pastor, the Wiccan, and myself could remember the entire night for the most part.

But what did it matter? There was no evidence the next morning, save for bleached white wooden floors of the Sanctuary of the Holy Brethren and the smashed insides of the church. The boys would go on to tell stories but without a body, the townsfolk would never be convinced, with their fathers mostly upset at the wasted ammunition, “shooting at ghosts in the wood”.

Part of me thought that the encounter who have improved my relations with Pastor Oaken but the following day, he remained as stone face as ever, directing the three Hudson boys on repairing the windows from the wind storm. For the following two years I lived amongst him, he never as much gave a nod when I mentioned the infamous night to him.

But Oaken never did replace or repaint the floorboards, declaring the church’s hastily-done renovation as an allegory for the nineteenth century’s goal: the rejuvenation of civilization in the face of nature’s unforgiving quest to destroy that which sins—humanity. He was so moved by the plant-based experience that he became a farmer after collecting a few dormant seeds left by the dark figures who grabbed their sister witch. He had spent a day scraping the seed remnants off the floorplanks and from the edges of the windowsill, managing to infuse the local soil with reproduced seed pods, grown inside the shell of a walnut. I wanted to stop him from meddling with whatever the witches of Boonestail truly were, but Oaken was, if nothing else, his own man. In another life, perhaps the two of us could have bonded over our shared fascination with nature.

The sheriff died of consumption (tuberculosis) the following spring after volunteering for a military campaign to spy on the Seminole Indian population of Florida. I attended his town funeral where his nephew gave a nice speech about his uncle’s bravery during the war. I was offered to give final words and did, recalling many dinners with Tiberius and his lovely widow Leena over the years and how comforting the sheriff always tried to make everyone feel.

Fortunately for me, the Wiccan was happy to discuss theories on most nights thereafter. Sometimes I would bring a bottle of brandy and my sparse collection of autopsy sketches and notes to her quarters, where we would sit by the fire and ponder how such creatures could exist. We never came to any solid conclusions. Calling them witches worked better than plant-humanoid masses of toxic fungus. But as the days passed and Oaken grew more and more passionate about the plight of humanity’s everlasting battle against nature, I saw my time in Boonestail coming to an end. Letters from home finally began to drift to my post office and the aches and pains of the homestead were calling. Besides, job offers floated in with my mother and cousin’s letters, including one from the New York Hospital’s Lunatic Asylum only a day from home. Temptation began packing my bags before I had fully made up my mind.

By the summer of 1811, it had been settled and I was moving back home to the Hudson River almost two years after the encounter. I said my goodbyes to the Wiccan, gifting her the title to my office space, nearly three times the size of her shop. I bought a campfire bundle from the Hudson brothers and wished them the best, especially the brave doctor’s assistant Christopher.

On horseback out of Boonestail (my supplies already shipped on a carriage two days earlier), I passed by Oaken’s church, now taller than I remembered, the spires more slanted like intruder-proof metal fencing. The outside was blinding white in the midday sun, “a beacon of fortitude” as Oaken claimed and many white-robed followers rummaged about the grounds, now full of gardens filled with the pastor’s homemade soil. Oaken himself was in the fields, sweating through two layers of white linen while urging his mule plower to hurry the pace. Despite my resistance, the Sanctuary’s gardens were bountiful with swollen cherry-red tomatoes and thick heads of lettuce, among infant berry bushes guarded from rabbits and gophers at all time by toddlers with rakes. Although I never saw Oaken or his church again, I wished him the best as well. Him and those damned walnuts.

I worked at the Asylum for eight years, eventually marrying my mother of my children in an arranged marriage that worked out nicely. We had four boys and two girls, filling our house along the Hudson with lots of love and boundless energy that kept me on edge as a father and doctor for the next two decades.

As the children grew older, my field shifted from intensive care of ten to twenty patients to being the overseeing manager of hundreds of ill peoples stricken by the everpresent Manhattan poverty. The stench of alcohol in every waiting room or hospital jail cell was nauseating, making me recall the events of 1809 so vividly for the first time in decades. Shortly after the illness of our second oldest boy, Reymond, I retired from my head role at the Asylum and joined the new Male Building board at Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in a much more passive role. I remained on the board for seven years, often walking the asylum’s lovely gardens and reminding myself of my strolls through Boonestail. It was funny. In those days, I was discontent with small town farmland and their smells were mostly the same.

Fortune found me after the death of my parents in 1838, providing me with the financial spark to create my own institution facilitated by medicinal practices I learned from the Wiccan along with intensive, serenity-based care I found at Bloomingdale. Hence, the Cawthon Sanatorium was born. Taken from my family’s medieval name, the building was erected near a small lake in southern Maryland, a place I had sketched out decades earlier on my initial trip into Boonestail. And that is where I sit as I write the final words of this summary.

I hope it does justice to the *REMOVED* and its archives. In my older age, I find myself increasingly searching for that which lies behind the normal line of human sight.

Therefore, I can proudly say—I am privileged to have been privy to a glimpse beyond the paranormal veil on November 10th, 1809…

_______________________

-DR ISAIAH HORNE-

APRIL the EIGHTH, 1842

BY 1850, BOONESTAIL HAD BEEN FLATTENED INTO THE BASIN-LINE TURNPIKE, A TOLL ROAD. THE FORMER TOWN BECAME A MAJOR CROSSROADS FOR TRAVELERS ACROSS THE SOUTHERN UNITED STATES, FADING INTO OBSCURITY WHILE THE INDUSTRIAL AGE RAGED ON.

IN 1861, THE CIVIL WAR BEGAN. THE BASIN-LINE TURNPIKE BECAME A VITAL PART OF MISSOURI’S FIGHTING FORCES, BEING THE BEST ROAD TO TRAVEL QUICKLY ACROSS THE BORDER STATE. DOZENS OF UNION AND CONFEDERATE LIVES WERE LOST DURING SKIRMISHES IN AND AROUND THE FORMER TOWN.

ONLY AFTER THE CIVIL WAR, IN THE RUBBLE AND DEATH LEFT IN ITS WAKE, WOULD BOONESTAIL RISE AGAIN. SEVERAL MISSOURIANS, GENERATIONS REMOVED FROM THE TOWN’S INHABITANTS CAME TOGETHER TO REBUILD THE TOWN, USING THE DISCARDED TURNPIKE AND ITS STONE FOUNDATION AS GROUDWORK.

THE WICCAN, NOTED AS M.A. IN DR. HORNE’S NOTES HAS NEVER BEEN IDENTIFIED.

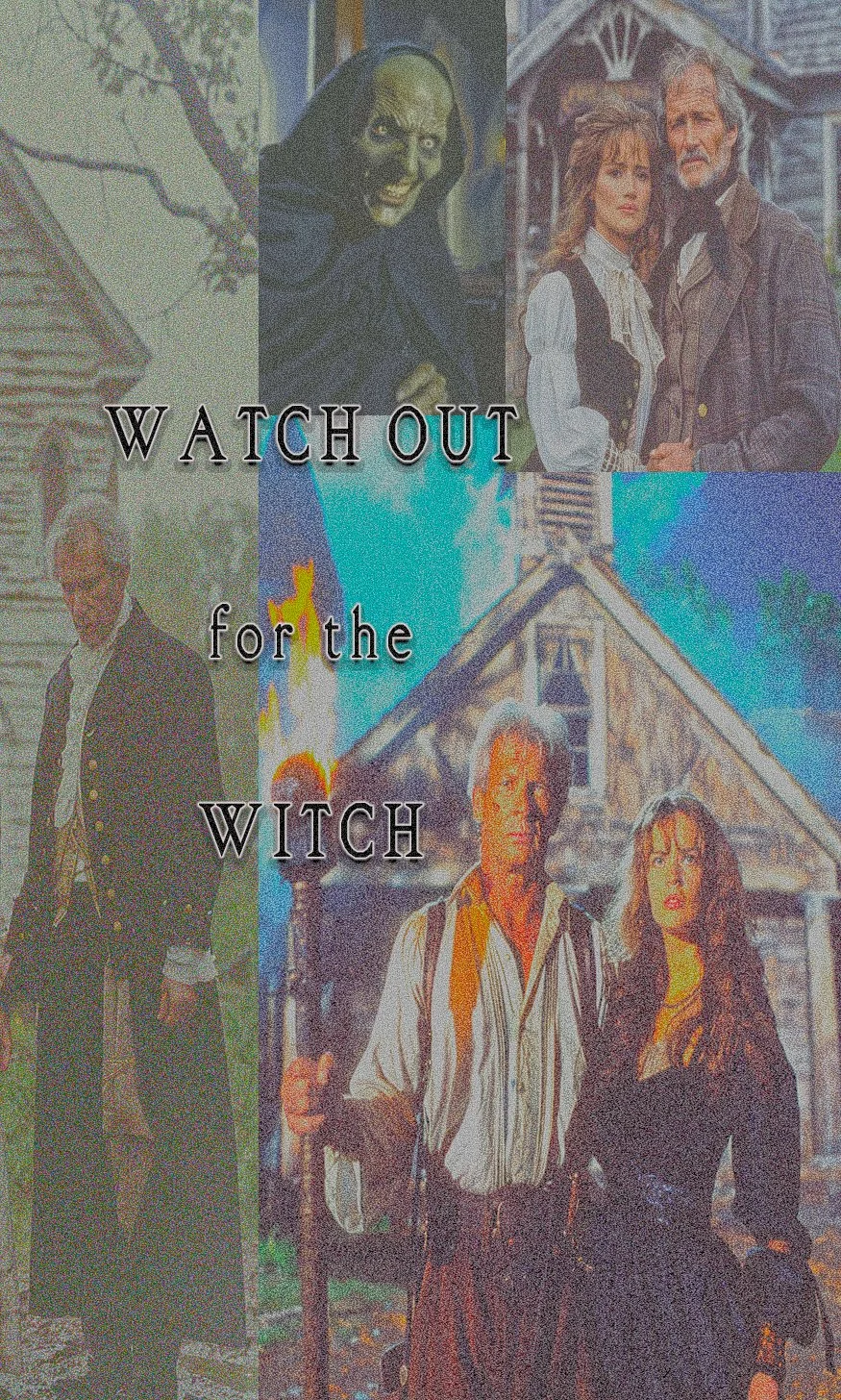

TODAY, DR. HORNE’S STORY IS BELIEVED TO BE A FANCIFUL TALL TALE, WITH MOST DETAILS EMBELLISHED OR OUTRIGHT FABRICATIONS. THERE HAVE BEEN THREE FILMS BASED ON THE BOONESTAIL WITCH ENCOUNTER, INCLUDING THE 1988 CULT CLASSIC TV MOVIE, WATCH OUT FOR THE WITCH, STARRING A GRIZZLED PAUL NEWMAN AND YOUNG JANE SEYMOUR—NEWMAN PORTRAYS AN AMALGAMATION OF DR. HORNE AND PASTOR OAKEN WHILE SEYMOUR PLAYS A FICTIONAL WICCAN CHARACTER WITH ANCESTRAL WITCH BLOOD. MOST RETELLINGS ENDS WITH DOCTOR HORNE AND THE WICCAN FALLING IN LOVE AND RUNNING AWAY TOGETHER. IN REALITY, NO EVIDENCE HAS BEEN FOUND OF THE WICCAN’S EXISTENCE, SAVE FOR THREE CANVAS DRAWINGS MADE BY HORNE SOMETIME BEFORE THE 1810S.

THIS FULL REPORT IS EXPECTED TO BE RELEASED ON *REMOVED*.

N.A.P. agents expect to return to the area for further historical research soon.

AS OF 2030, BOONESTAIL IS A TOWN OF 6,000 AND A POPULAR TOURIST ATTRACTION FOR LOVERS OF AMERICAN HISTORY, WITCH TALES, AND WALNUT WAFFLE PIES.